Command Palette

Search for a command to run...

By Integrating Data on Protein Sequences, three-dimensional Structures, and Functional Characteristics, a German Team Constructed a "panoramic View" of Human E3 Ubiquitin Ligases Based on Metric learning.

In organisms, the timely degradation and renewal of cellular proteins is crucial for maintaining protein homeostasis. The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) is a core mechanism regulating signal transduction and protein degradation. Within this system, E3 ubiquitin ligases, as key catalytic units, are responsible for recognizing specific substrates and catalyzing ubiquitin labeling, thereby regulating protein degradation, localization, and functional state. Furthermore, E3 ligases also regulate immune and inflammatory pathways. Due to their tissue-specific expression and association with developmental and metabolic syndromes (including cancer progression), E3 ligases have become promising drug targets, particularly for targets that were previously difficult to drug.

Compared to E1 (approximately 10 types) and E2 (approximately 50 types) enzymes, a large number of human E3 ligases (approximately 600 types) have been identified. Nevertheless, many human E3 ligases are still only partially characterized, and a large number remain hypothetical or unknown. To date,The studied E3 ligases exhibit high heterogeneity.This makes it one of the most diverse enzyme classes, creating a bottleneck for pattern recognition and large-scale research. Therefore, detailed characterization and analysis of the human E3 ligase genome—the complete set of E3 ligases encoded by the human genome—is crucial for a comprehensive understanding of their biological functions.

In this context,A research team from Goethe University in Germany has classified the "human E3 ligome."It integrates multi-level data, including protein sequences, domain composition, three-dimensional structure, function, and expression patterns.The team's classification method is based on the metric-learning paradigm and employs a weakly supervised hierarchical framework to capture the true relationships between the E3 family and its subfamilies.This approach expands upon the traditional classification of E3 enzymes (RING, HECT, and RBR classes), distinguishes between multi-subunit complexes and monomeric enzymes, and maps E3 enzymes to substrates and potential drug targets.

The related research findings, titled "Multi-scale classification decodes the complexity of the human E3 ligome," have been published in Nature Communications.

Research highlights:

* Mapping the domain architecture, three-dimensional structure, function, substrate network, and small molecule interactions of existing E3 ligases into a classification framework to gain general and family-specific insights.

* The developed multi-scale classification framework covers both typical and atypical E3 mechanisms, providing a complete roadmap for understanding the broad biological landscape of E3 ligases.

* Opens new avenues for developing drug intervention strategies based on E3-substrate networks.

Paper address:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-67450-9

Follow our official WeChat account and reply "E3 enzyme" in the background to get the full PDF.

More AI frontier papers:

https://hyper.ai/papers

Dataset: Constructing human E3 ubiquitin ligase data

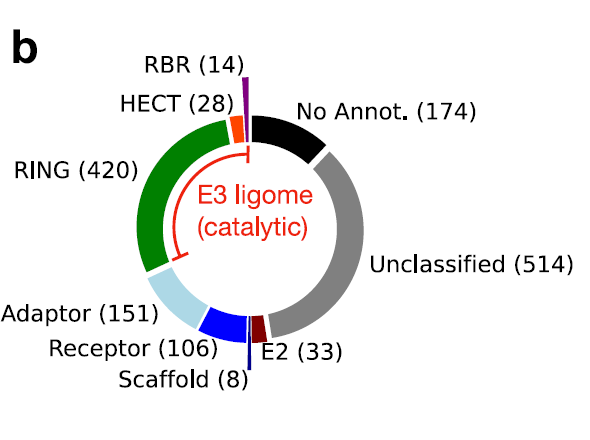

The research team first integrated human E3 ubiquitin ligase data from eight independent data sources.Including previous literature reports and public databases (E3Net, UbiHub, UbiNet 2.0, UniProt, BioGRID, etc.), a preliminary dataset of 1,448 protein entries was formed. Duplicate and potentially false positive entries were removed through cross-comparison and consistency scoring of data from various sources. Subsequently, using the RING, HECT, and RBR catalytic domain features provided by InterPro, 462 high-confidence catalytic E3 ubiquitin ligases were screened, forming the final human E3 ligase genome.

In multi-subunit E3 complexes (such as Cullin-RING ligases), three functionally distinct subunits (scaffold protein, aptamer protein, and receptor protein) work together to localize E2~Ub molecules to specific substrates. Large, rigid, and centrally located scaffold proteins (such as the Cullin family, Cul1–Cul5) organize the entire ligase complex by simultaneously binding to the docking sites of the catalytic RING finger domain subunit and the aptamer/receptor. The aptamer protein bridges the modules, connecting the N-terminal docking face of the scaffold protein to individual substrate receptors. The receptor protein determines substrate specificity, directly recognizing and binding to degradation signals (degrons) on the substrate to determine which substrates will be ubiquitinated (e.g., Skp2, Keap1, VHL).The research team independently annotated and categorized three subunits: 151 aptamers, 106 receptors, and 8 scaffold proteins.They also used their protein-protein interactions (PPIs) to map the substrates of multi-subunit E3.

Subsequently, in the catalytic domain screening stage, researchers used catalytic ability as the core criterion to rigorously filter candidate proteins.Using domain databases such as InterPro, the system identified key catalytic domains directly related to E3 activity, including RING, HECT, and RBR.Only proteins that explicitly contain these domains and support their ubiquitin-ligating function at the sequence and structural levels are retained to construct the final "catalytic E3 ligase". This process effectively eliminates accessory proteins that only participate in regulation but do not have direct catalytic ability, thereby ensuring the functional consistency of the core E3 set.

A multi-scale classification framework based on metric learning

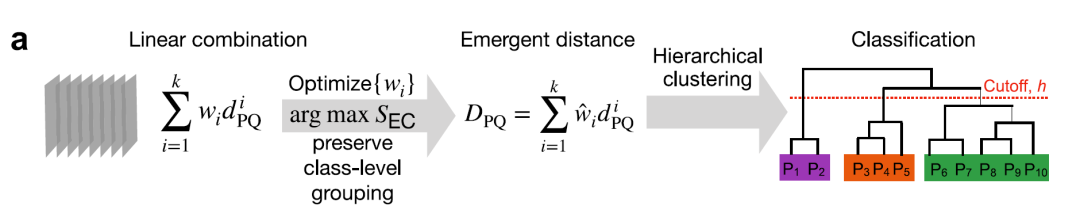

To capture the complex relationships within the human E3 ligase genome,Researchers used machine learning methods to learn an Emergent distance metric.The overall framework is shown in the following diagram:

① Multi-scale distance measurement

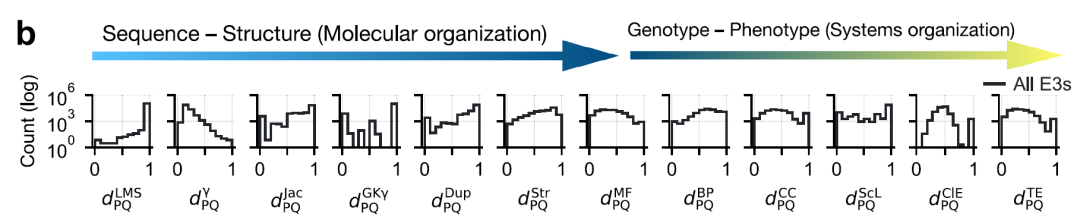

Researchers encoded pairwise relationships between E3 ligases by calculating 12 different distances.These distances cover multiple granular levels: primary sequence, domain architecture, tertiary structure, function, subcellular localization, and cell line/tissue expression.All distance metrics are scaled to the [0,1] interval for comparison and combination, as shown in the figure below:

* Sequence level: Local matching score (LMS) distance (without pairwise matching) and alignment-based γ distance were used.

* At the domain architecture level: three distances were calculated—Jaccard distance, Goodman–Kruskal γ distance, and domain repetition distance.

* 3D structural level: using the AlphaFold2 model TM-score

* Functional level: The functional distance between proteins and P and Q is measured using semantic similarity of GO annotations, covering three ontologies: * Molecular function (MF), biological process (BP), and cellular component (CC).

* Subcellular localization distance

* Co-expression distance between tissues and cell lines

②Metric optimization, clustering, bootstrapping and classification

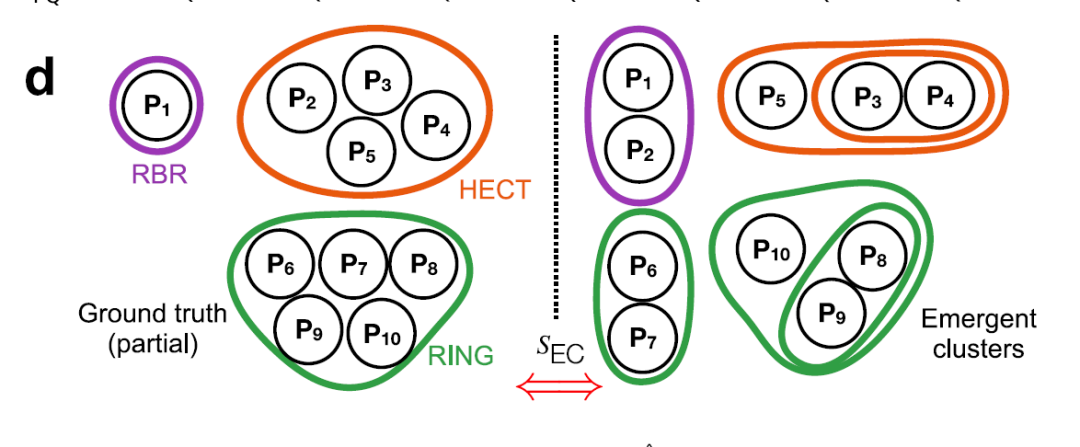

The four main distances (γ, Jaccard, structure, and molecular function) are weighted and integrated, with the weights optimized through weakly supervised learning and the element center similarity index (SEC), as shown in the figure below, to obtain the optimal combined index.

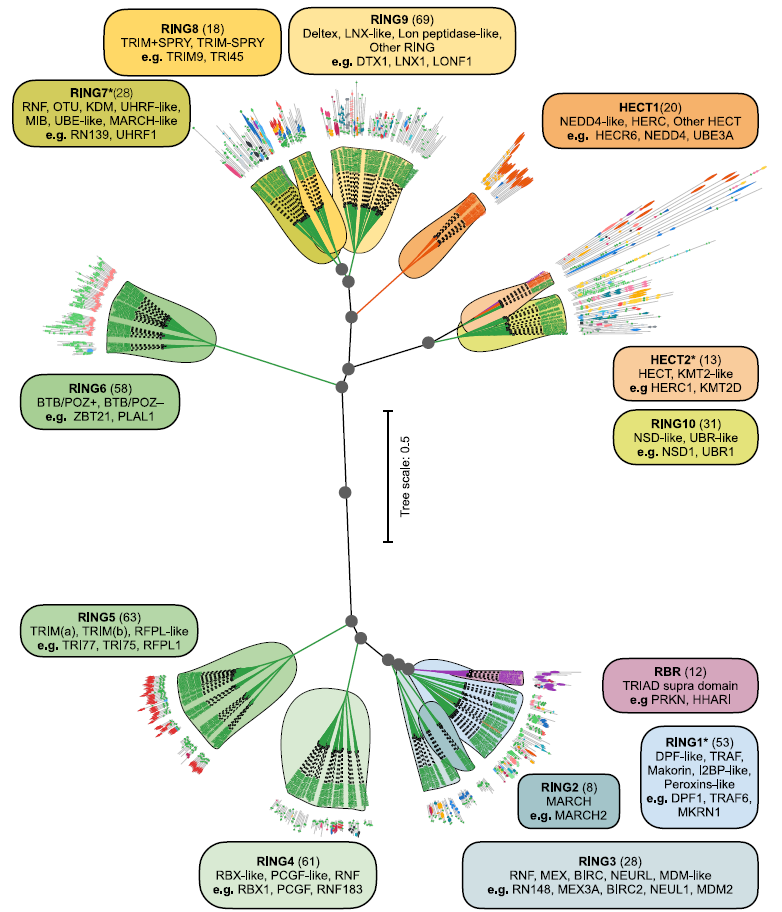

Hierarchical clustering was performed using Ward's minimum variance method.Support is calculated using the bootstrapping method to generate the final E3 dendrogram. Optimal emergent clusters are obtained with a tree slicing threshold h = 0.25, systematically dividing the 462 E3 clusters into 13 families: 10 RING families, 2 HECT families, and 1 RBR family, as shown in the figure below.

Each family undergoes further manual analysis of sequence and domain features to identify subfamilies and aberrant proteins.

③ Small molecule clustering and binding probability

Integrated 2D UMAP projection for small molecule clusteringTwenty representative small molecular clusters were identified by combining local density peaks.The probability of each cluster binding to the E3 protein was quantified by log-transformed propensities (LPij), providing guidance for subsequent PROTAC development and targeted small molecule design.

A detailed assessment of the integrity of the human E3 ligase genome was provided.

①Detailed organization of the human E3 ligase genome

To address the challenges posed by the diverse strategies and inconsistent definitions employed in existing studies when organizing the E3 system, this research team explicitly defined the catalytic components of the E3 system as polypeptide sequences containing one or more catalytic domains. This objective standard enables proper annotation and targeted analysis of E3.Ultimately, the researchers found that 462 polypeptide sequences across the entire dataset contained at least one catalytic domain.These polypeptides constitute a finely organized human E3 ligase genome, as shown in the figure below:

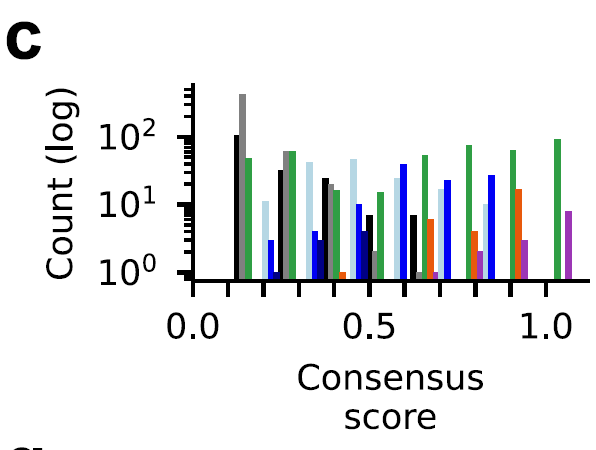

To verify the reliability of the sorting process, the researchers defined a consensus score for each protein based on its frequency of occurrence in datasets from different sources.The results showed that HECT and RBR class E3 ligases were highly consistent in the dataset (consensus score ≥ 0.6, orange and purple bars).The consensus scores for the RING class (green bars) are widely distributed, indicating a challenge in annotation, as shown in the figure below:

Using this method, researchers minimized false positives and true negatives, included highly reliable catalytically active E3s, and considered pseudo-E3s and other E3s whose catalytic activity had not been verified, thus providing a detailed assessment of the integrity of the human E3 ligase genome.

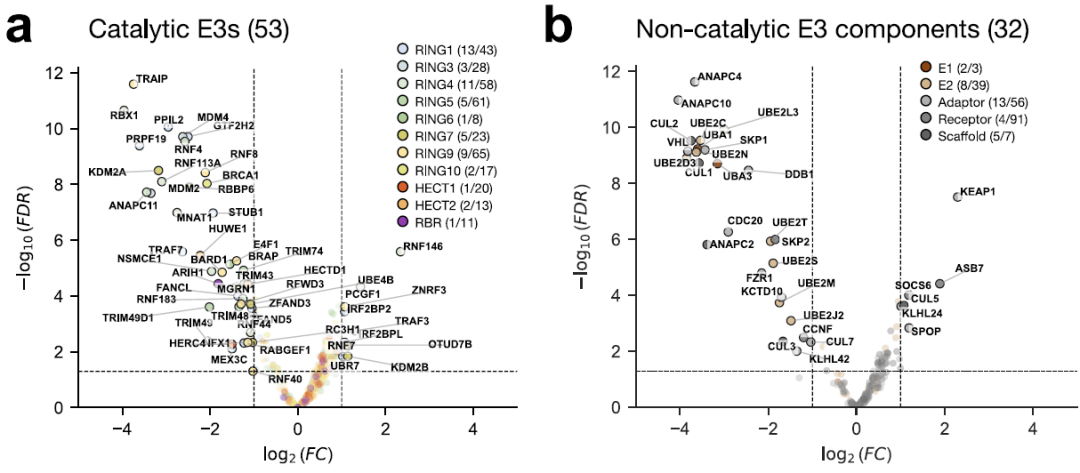

② Functional differentiation of human E3 ligase

To assess the function of the human E3 ligase, researchers screened for CRISPR-Cas9 deletion in the UPS gene, using cell viability as the primary phenotype. The results showed that...A total of 53 catalytic and 32 non-catalytic E3 components were identified as being crucial for cell viability.As shown below:

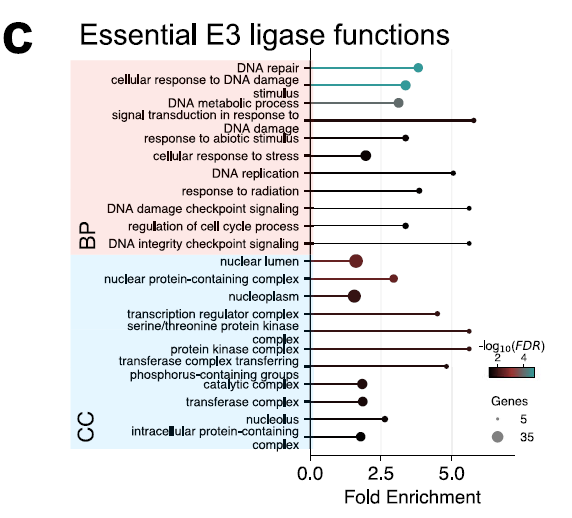

GO analysis of 53 key E3s showed that they were significantly enriched in nuclear components and in DNA damage, replication and repair processes, as shown in the figure below, indicating their central role in maintaining genome integrity and nuclear regulation. These results reveal the E3 components that are essential for cell survival.

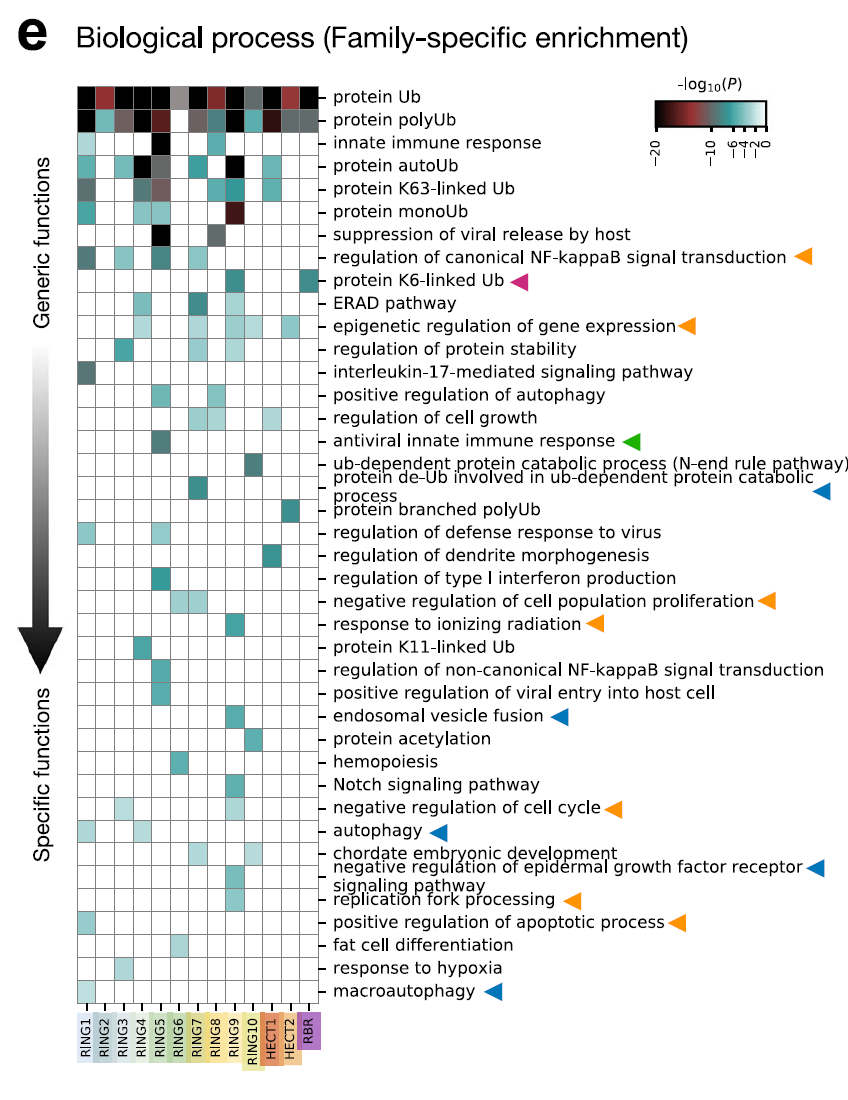

GO enrichment analysis was performed on 13 E3 families using Metascape, and the network was visualized using Cytoscape. The results show that...Different families have distinct roles in substrate selection, cellular localization, and catalytic function.As shown in the figure below. For example, RBR family members RNF14, RNF144A, and PRKN are specific for K6-linked ubiquitin. The K6-linked chain can label stalled RNA-protein cross-linked complexes (RNF14), the DNA-sensing adapter STING (RNF144A) for activating interferon signaling, and damaged mitochondria for clearance (PRKN). Similarly,TRIM E3s (RING5) are significantly enriched in antiviral innate immune responses, and they regulate the activity of pattern recognition receptors in cells.Such as reactions mediated by RIG-1 and MDA5.

④ Druggability map of human E3 ligases

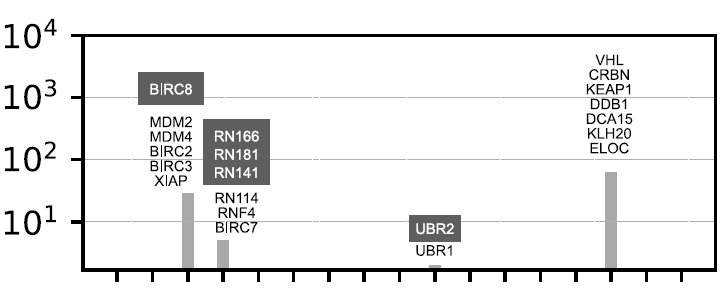

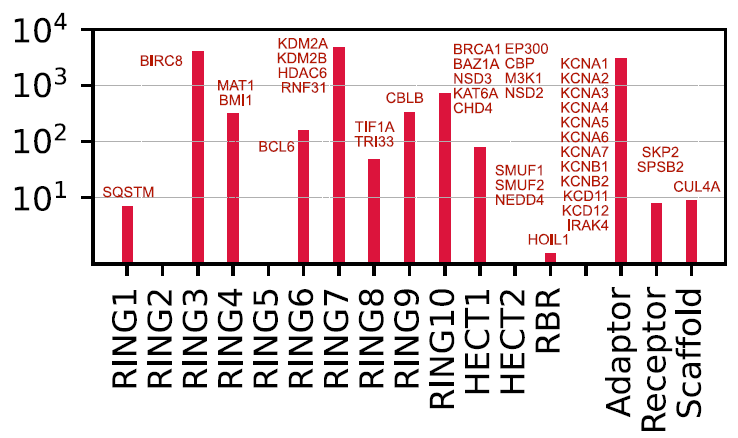

To explore potential therapeutic pathways based on proximal action, researchers mapped existing E3 operands derived from known protein degradation-targeting chimeras (PROTACs) and E3 binders to various E3s and their families. Currently, only 16 proteins (9 catalytic E3s and 7 adapters) can be directly targeted by existing E3 operands. Most of the designed E3 operands target adapter proteins (such as VHL and CRBN), while only a very small number directly target catalytic E3s (such as XIAP, MDM2/4/7, and BIRC2/3/7).

Nearest neighbor analysis using the human E3 ligase from this study revealed five highly correlated proteins (BIRC8, RN166/181/141, and UBR2).As shown below:

Because of their high structural similarity (often homologous proteins), existing E3 operands can be reused to target these proteins.Mapping small molecule E3 binders has given researchers access to a potential set of compounds that can target an additional 25 E3 molecules and 15 non-catalytic components.This discovery uncovers untapped targets, providing a pathway for the rational design of lead compounds for the E3 operand, as shown in the figure below:

Multi-scale frameworks provide powerful tools for the analysis of complex biological systems.

In the field of machine learning, a multi-scale framework refers to a modeling method or analysis strategy that can process data at different levels of abstraction or different feature scales. It is not a fixed algorithm, but a design concept used to integrate local and global information, coarse-grained and fine-grained features, thereby improving the expressiveness and generalization ability of the model.

The value of the multi-scale classification framework is not limited to the systematic review of the E3 ligase family itself; its more significant meaning lies in providing a transferable and scalable paradigm for omics integration. This cross-scale integration approach naturally enables it to be extended to other multimodal omics data, providing a universal tool for the systematic analysis of complex biological systems.

For example, the cell is the basic unit of life, and its function and fate are determined by complex molecular networks. While traditional deep learning methods perform well in cell type identification from single-cell transcriptome data, they lack biological interpretability. On October 20, 2025, researchers from the National Protein Science Center of China (Beijing) and Tsinghua University proposed Cell Decoder, a multi-scale interpretable deep learning framework that integrates biological prior knowledge.It enables hierarchical characterization and reasoning from genes and pathways to biological processes, providing a new approach to decoding cell types at the single-cell level. Cell Decoder constructs a cross-scale biological knowledge graph by embedding protein interaction networks, gene-pathway mappings, and pathway hierarchical relationships into a graph neural network architecture.The research team systematically evaluated Cell Decoder against nine mainstream methods on human and mouse samples from seven publicly available single-cell datasets. The results showed that Cell Decoder ranked first in both prediction accuracy (0.87) and Macro F1 (0.81), and maintained stable performance even under complex conditions such as noise perturbation, cell type imbalance, and cross-batch distribution shift.

Paper Title:Cell Decoder: decoding cell identity with multi-scale explainable deep learning

Paper address:

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s13059-025-03832-y

From a longer-term perspective, the multi-scale framework can be further integrated with spatial proteomics data, small molecule drug libraries, and chemical spatial information, thereby breaking down data barriers between basic biological research, disease mechanism analysis, and translational applications. With the continuous accumulation of multi-omics data, this framework is expected to play an increasingly important supporting role in life science research and biomedical innovation.

References:

1.https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-67450-9

2.https://blog.csdn.net/qazplm12_3/article/details/153948711

3.https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s13059-025-03832-y