Command Palette

Search for a command to run...

AudioSAE: Towards Understanding of Audio-Processing Models with Sparse AutoEncoders

AudioSAE: Towards Understanding of Audio-Processing Models with Sparse AutoEncoders

Georgii Aparin Tasnima Sadekova Alexey Rukhovich Assel Yermekova Laida Kushnareva Vadim Popov Kristian Kuznetsov Irina Piontkovskaya

Abstract

Sparse Autoencoders (SAEs) are powerful tools for interpreting neural representations, yet their use in audio remains underexplored. We train SAEs across all encoder layers of Whisper and HuBERT, provide an extensive evaluation of their stability, interpretability, and show their practical utility. Over 50% of the features remain consistent across random seeds, and reconstruction quality is preserved. SAE features capture general acoustic and semantic information as well as specific events, including environmental noises and paralinguistic sounds (e.g. laughter, whispering) and disentangle them effectively, requiring removal of only 19-27% of features to erase a concept. Feature steering reduces Whisper's false speech detections by 70% with negligible WER increase, demonstrating real-world applicability. Finally, we find SAE features correlated with human EEG activity during speech perception, indicating alignment with human neural processing. The code and checkpoints are available at https://github.com/audiosae/audiosae_demo.

One-sentence Summary

Researchers from Huawei Noah’s Ark Lab propose Audio SAEs for interpreting Whisper and HuBERT, revealing stable, interpretable features that disentangle acoustic and paralinguistic events; feature steering cuts false speech detection by 70%, and features align with human EEG, enabling practical, neuroscience-grounded audio analysis.

Key Contributions

- We train Sparse Autoencoders on Whisper and HuBERT encoder layers, providing the first large-scale interpretability analysis of audio representations and releasing code and checkpoints to enable further research.

- SAE features show high stability across random seeds (over 50% consistent) and effectively disentangle acoustic, semantic, and paralinguistic concepts—such as laughter or whispering—with only 19–27% feature removal needed to erase a concept.

- We demonstrate practical utility by steering Whisper to reduce false speech detections by 70% with minimal WER impact, and show neuroscientific relevance through correlations between SAE features and human EEG activity during speech perception.

Introduction

The authors leverage sparse autoencoders (SAEs) to interpret large audio models like Whisper and HuBERT, addressing a gap in audio representation analysis where SAEs have been underexplored despite their success in NLP and vision. Prior work in audio interpretability has focused on neuron-level explanations or narrow domains like music, lacking systematic evaluation across speech models or practical steering applications. Their main contribution is the first large-scale SAE analysis of audio models, releasing trained SAEs and demonstrating that the extracted features are stable, semantically meaningful, and useful for real-world interventions such as reducing hallucinations in Whisper and correlating with human neural activity.

Dataset

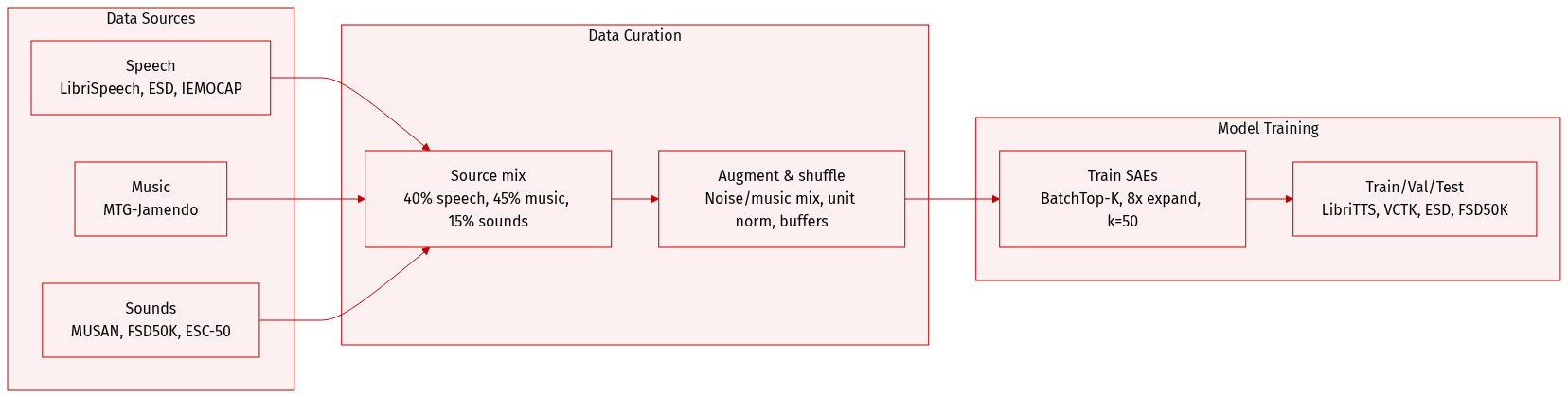

The authors use a diverse 2,800-hour audio corpus to train Sparse Autoencoders (SAEs) on HuBERT-base and Whisper-small, extracting activations from every encoder layer. The dataset combines speech, music, and environmental sounds from 15+ public sources, weighted to bias training toward non-speech content: ~40% speech, 45% music, 15% environmental sounds.

Key subsets:

- Speech: LibriSpeech, LibriHeavy, ESD, Expresso, CREMA, MELD, IEMOCAP

- Music: MTG-Jamendo

- Environmental sounds: MUSAN, WHAM, FSD50K, Nonspeech7k, DEMAND, VGGSound, VocalSound, ESC-50

Each dataset is sampled proportionally to its configured weight and size. Activations are extracted using a dynamic batching strategy: audio is randomly drawn per dataset weight, then activations are buffered and shuffled for randomized sampling. Batches contain 2,500 vectors (50 seconds of audio), enabling efficient training over 200,000 steps.

Processing includes:

- Online augmentation: noise (p=0.05) and music (p=0.025) mixed at 0–20 dB SNR

- Unit normalization of input activations

- Memory-mapped buffers for activation storage and shuffling

- Multi-GPU parallelization across 8 V100s for base model inference and SAE training

SAEs use BatchTop-K architecture with L2 reconstruction loss, Adam optimizer (lr=2e-4), and linear sparsity warmup over 10,000 steps. Expansion factor 8x and sparsity k=50 were selected as optimal based on reconstruction, sparsity, and alive feature trade-offs.

For downstream analysis, the authors use:

- Speech classification: LibriTTS (gender), VCTK (accents), ESD (emotion)

- Hallucination evaluation: FSD50K (filtered), MUSAN, WHAM (non-speech), LibriSpeech (speech recognition baseline)

- Domain specialization detection: frame-level (τ=0.2, 0.1, 0.04) and audio-level (τ=0.5, 0.3) thresholds across domain pairs to identify cross-modal feature roles.

Method

The authors leverage a Sparse Autoencoder (SAE) to disentangle polysemantic activations in audio representation models, specifically Whisper and HuBERT, into interpretable, monosemantic features. The SAE architecture operates by encoding input activations x into a sparse latent representation via a non-linear transformation and then reconstructing the original activations. The encoding and decoding functions are defined as:

f(x)=σ(Wencx+benc),x^(f(x))=Wdecf(x)+bdec,where σ denotes a sparsity-inducing activation function. Among Jump-ReLU, Top-k, and Batch-Top-k, the authors select Batch-Top-k for its superior balance of reconstruction fidelity and sparsity. Training is performed using an L2 reconstruction loss without auxiliary regularization, emphasizing the model’s ability to recover meaningful features through sparsity alone.

To evaluate the robustness and consistency of learned features, the authors introduce a distributional similarity metric based on Intersection-over-Union (IoU) over binary activation patterns across datasets. Two features ak and bm are deemed semantically similar if their activation overlap exceeds a threshold θ. Feature coverage c(A,B) quantifies the proportion of features in set A that are covered by set B, enabling comparisons across random seeds, layers, and model architectures. Redundancy is assessed by identifying duplicated features within a single SAE—those with high IoU to other features in the same set.

Domain specialization is analyzed by attributing features to speech, music, or environmental sounds based on activation frequency at both frame and audio levels. A feature is assigned to domain i∗ if its activation frequency in that domain exceeds all others by at least a threshold τ, with graded confidence levels derived from a progressive threshold set. Features failing to meet any threshold are labeled unassigned; those with zero activation across all domains are marked dead. Final domain assignments are aggregated across all domain combinations and visualized via t-SNE projections of encoder weights, with color intensity modulated by threshold index to reflect confidence.

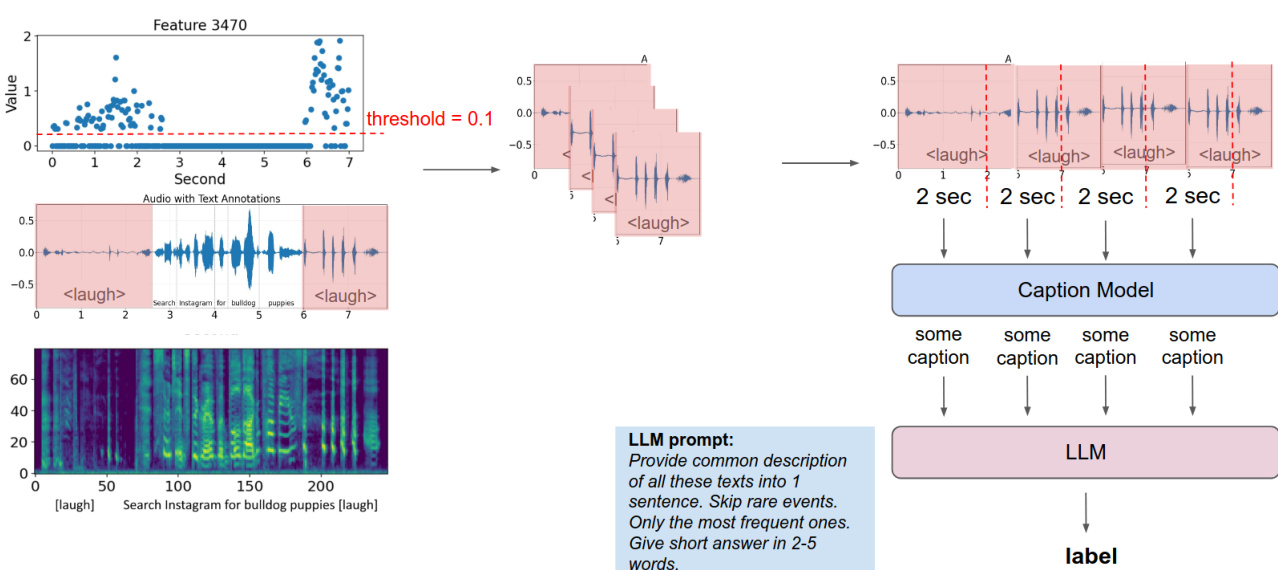

Refer to the framework diagram for an illustration of how SAE-derived features are interpreted and applied. The figure shows Feature 3470’s activation pattern over time, thresholded at 0.1, aligned with audio segments annotated with . These activations are fed into a caption model, which generates short descriptions, and then into an LLM for final labeling. This pipeline demonstrates how sparse, interpretable features can be mapped to semantic events in audio, enabling downstream interpretability and control.

For hallucination reduction in Whisper, the authors implement SAE steering: a linear intervention in the latent space that biases activations away from hallucination-prone regions. They identify top-k hallucination-associated features via logistic regression on SAE activations from non-speech data, using Whisper’s internal no_speech_prob as a proxy label. The steering vector sSAE is constructed by negating the sign of the top-k regression coefficients, ensuring opposition to hallucination-promoting features. During inference, activations are modified as:

actsteered=x^(f(act)+αsSAE),where α controls steering intensity. This intervention shifts the distribution of no_speech_prob toward 1 for non-speech inputs and toward 0 for speech inputs, effectively reducing false positives while preserving true positives.

Experiment

- SAEs trained on Whisper and HuBERT show over 50% feature consistency across random seeds, preserving reconstruction quality while capturing acoustic, semantic, and paralinguistic content like laughter or whispering.

- Feature disentanglement is effective: removing 19–27% of features can erase specific concepts such as vowel pronunciation, though phonetic information is more distributed than in text-based SAEs.

- SAE features enable practical steering: suppressing top-100 features reduces Whisper’s false speech detection by 70% with minimal impact on word error rate, demonstrating real-world utility.

- Classification tasks reveal that a small subset of features (10–150 for binary tasks) captures most task-relevant information, while erasing complex traits like accents requires suppressing thousands, indicating redundancy.

- Frame-level analysis identifies features tied to specific events (e.g., speech boundaries, laughter, sneezing), while auto-interpretation uncovers unannotated sounds like alarms or birds chirping, though speech phonemes are often generalized.

- Domain specialization varies by model: Whisper shows strong audio-level music specialization peaking mid-network, while HuBERT distributes specialization more evenly; speech features dominate mid-layers in both.

- SAE features correlate with human EEG activity during speech perception, particularly at the Pz electrode, with significant temporal alignment suggesting alignment with neural processing.

- Cross-model comparisons show low feature alignment between Whisper and HuBERT due to differing training objectives, but high inter-layer stability in later layers.

- Evaluation confirms SAEs are robust and interpretable, though performance varies by task; no single metric suffices, requiring multi-faceted assessment for application-specific suitability.

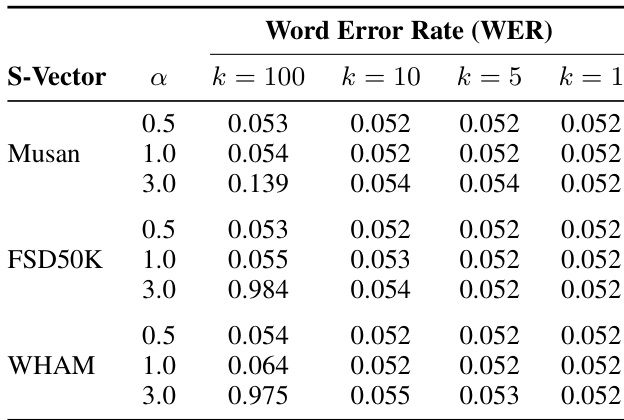

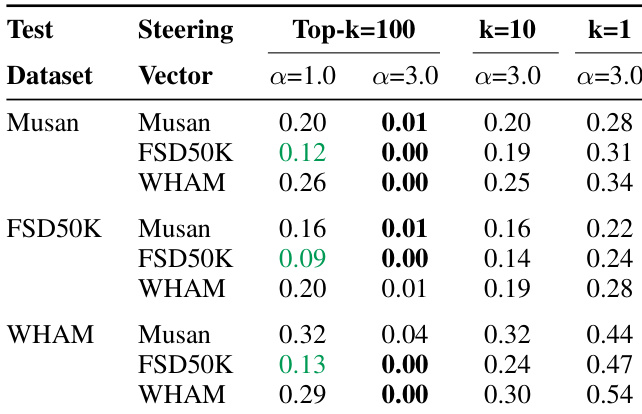

Results show that steering Whisper’s SAE features using top-100 features with moderate strength (α=1.0) reduces false positive speech detection by up to 70% across non-speech datasets, while maintaining near-baseline speech recognition accuracy. Aggressive steering (α=3.0) achieves near-zero false positives but risks degrading model performance, highlighting a trade-off between hallucination suppression and functional integrity. The effectiveness varies by dataset and steering vector source, with FSD50K-derived vectors yielding the strongest suppression.

The authors use SAE-based steering to significantly reduce false speech detections in Whisper, achieving up to a 70% drop in false positive rate across non-speech datasets while maintaining near-original speech recognition accuracy. Results show that moderate steering strength (α=1) offers the best trade-off, whereas aggressive steering (α=3) severely degrades word error rate, indicating a clear safety-performance balance.

The authors use Sparse Autoencoders to extract interpretable features from Whisper and HuBERT audio models, finding that over half of the features remain consistent across random seeds and that these features effectively disentangle acoustic and semantic concepts. Results show that steering based on these features reduces false speech detections by 70% with minimal impact on recognition accuracy, and that some features correlate with human EEG activity during speech perception, suggesting alignment with neural processing.

The authors use SAE steering to reduce false speech detections in Whisper, achieving up to a 70% drop in false positive rate across non-speech datasets while maintaining near-identical word error rates on clean speech. Results show that moderate steering strength (α=1) with top-100 features offers the best trade-off between hallucination suppression and recognition accuracy, whereas aggressive steering (α=3) risks degrading speech comprehension.

The authors use SAE steering to reduce false speech detections in Whisper, finding that moderate steering (α=1, k=100) cuts false positives by 70% with minimal impact on WER, while aggressive steering (α=3) severely degrades speech recognition. Results show that steering effectiveness depends on both the dataset used to derive the vector and the number of features adjusted, with Musan and FSD50k yielding more stable WER than WHAM under strong steering.