Command Palette

Search for a command to run...

Towards Autonomous Mathematics Research

Towards Autonomous Mathematics Research

Abstract

Recent advances in foundational models have yielded reasoning systems capable of achieving a gold-medal standard at the International Mathematical Olympiad. The transition from competition-level problem-solving to professional research, however, requires navigating vast literature and constructing long-horizon proofs. In this work, we introduce Aletheia, a math research agent that iteratively generates, verifies, and revises solutions end-to-end in natural language. Specifically, Aletheia is powered by an advanced version of Gemini Deep Think for challenging reasoning problems, a novel inference-time scaling law that extends beyond Olympiad-level problems, and intensive tool use to navigate the complexities of mathematical research. We demonstrate the capability of Aletheia from Olympiad problems to PhD-level exercises and most notably, through several distinct milestones in AI-assisted mathematics research: (a) a research paper (Feng26) generated by AI without any human intervention in calculating certain structure constants in arithmetic geometry called eigenweights; (b) a research paper (LeeSeo26) demonstrating human-AI collaboration in proving bounds on systems of interacting particles called independent sets; and (c) an extensive semi-autonomous evaluation (Feng et al., 2026a) of 700 open problems on Bloom's Erdos Conjectures database, including autonomous solutions to four open questions. In order to help the public better understand the developments pertaining to AI and mathematics, we suggest codifying standard levels quantifying autonomy and novelty of AI-assisted results. We conclude with reflections on human-AI collaboration in mathematics.

One-sentence Summary

Google DeepMind researchers introduce Aletheia, a math research agent powered by Gemini Deep Think and novel inference scaling, enabling end-to-end natural language proof generation, verification, and revision; it autonomously solved open Erdős problems, generated research papers, and demonstrated human-AI collaboration in advanced mathematical discovery.

Key Contributions

- Aletheia introduces an autonomous math research agent that iteratively generates, verifies, and revises proofs in natural language, addressing the gap between competition-level problem solving and open-ended research by integrating advanced reasoning, inference-time scaling, and tool use like web search.

- The system achieves state-of-the-art performance on Olympiad benchmarks (95.1% on IMO-ProofBench) and PhD-level exercises, and demonstrates real research impact by autonomously solving four Erdős open problems and producing a fully AI-generated paper on eigenweights in arithmetic geometry.

- Aletheia enables human-AI collaboration in proving bounds on independent sets and contributes to multiple research papers, while the authors propose a standardized taxonomy to classify AI autonomy and novelty in mathematical results to improve transparency and public understanding.

Introduction

The authors leverage advances in large language models to bridge the gap between competition-level math problem solving and professional mathematical research, where problems require synthesizing vast literature and constructing long-horizon proofs—tasks that prior models often fail at due to hallucinations and shallow domain understanding. They introduce Aletheia, a math research agent that iteratively generates, verifies, and revises solutions using an enhanced Gemini Deep Think model, a novel inference-time scaling law, and tool integration like web search. Aletheia demonstrates capability across Olympiad, PhD-level, and open research problems, including fully autonomous derivation of structure constants in arithmetic geometry, human-AI co-authored proofs on particle systems, and semi-autonomous resolution of four Erdős conjectures—marking the first steps toward scalable AI-assisted mathematical discovery.

Method

The authors leverage a multi-agent orchestration framework, internally codenamed Aletheia, to address the challenges of autonomous mathematics research. This framework is built atop Gemini Deep Think and is designed to overcome the limitations of large language models in handling advanced, research-grade mathematical problems, which often require deep domain knowledge and rigorous validation beyond the scope of standard contest problems.

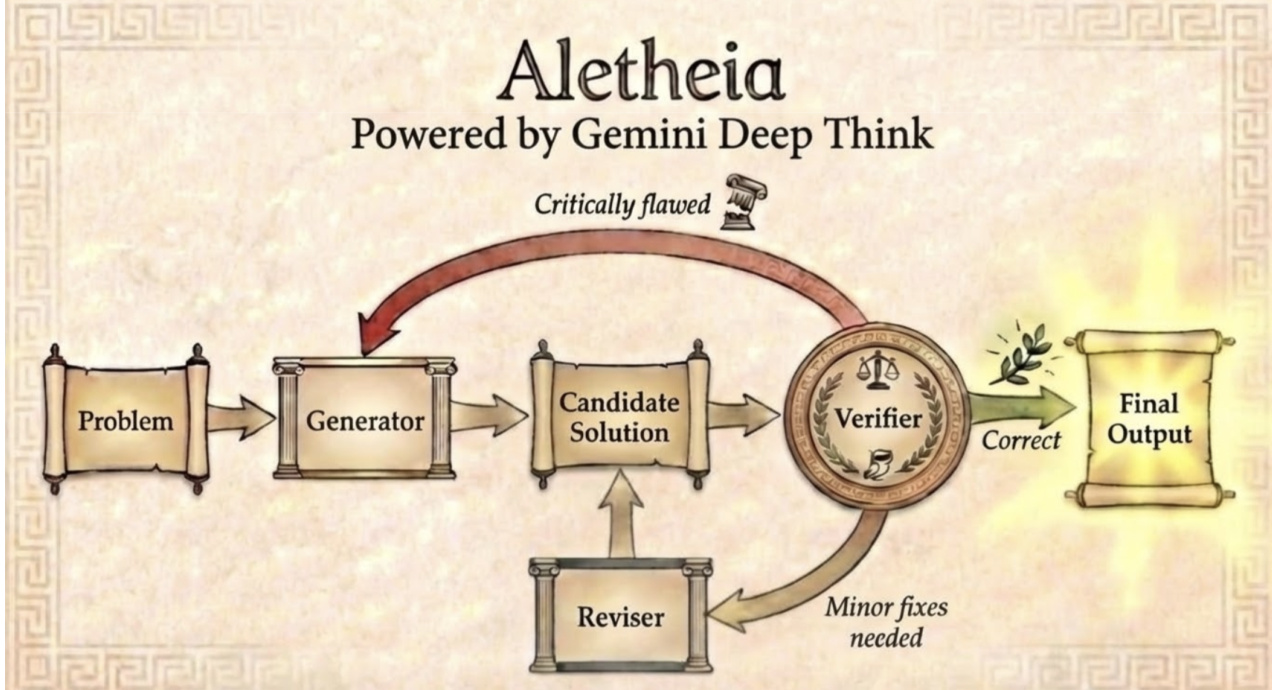

The core architecture of Aletheia consists of three tightly coupled subagents: a Generator, a Verifier, and a Reviser. The Generator is responsible for producing initial candidate solutions to a given mathematical problem. These candidates are then passed to the Verifier, which critically evaluates their correctness and logical soundness. If the Verifier identifies flaws, it routes the candidate back to the Reviser, which performs targeted refinements or minor fixes. This iterative loop continues until the Verifier approves a solution or a predefined attempt limit is reached. The entire process is designed to emulate the human mathematician’s cycle of conjecture, critique, and revision.

Refer to the framework diagram, which illustrates the flow of information and control between the subagents. The Generator initiates the process by receiving the problem statement and producing a candidate solution. The Verifier then assesses this solution, either approving it for final output or flagging it for revision. The Reviser, upon receiving feedback, modifies the candidate and resubmits it to the Generator for re-evaluation. This closed-loop design ensures that solutions are not only generated but also rigorously validated and refined, significantly enhancing the reliability of the output.

Experiment

- Gemini Deep Think achieved IMO gold by solving five of six 2025 problems, demonstrating strong performance under inference scaling, with accuracy improving significantly before plateauing.

- A more efficient model (Jan 2026) reduced compute needs by 100x while maintaining or improving performance, solving difficult IMO problems including 2024 P3 and P5 at high scales, though knowledge cutoff raises potential exposure concerns.

- On FutureMath (Ph.D.-level math), performance saturated at lower accuracy than IMO, with expert feedback highlighting persistent hallucinations and errors that limit research utility despite scaling.

- Tool use (especially internet search) substantially reduced citation hallucinations in Aletheia, though subtler misrepresentations of real papers persisted; Python integration offered minimal gains, suggesting baseline math proficiency is already high.

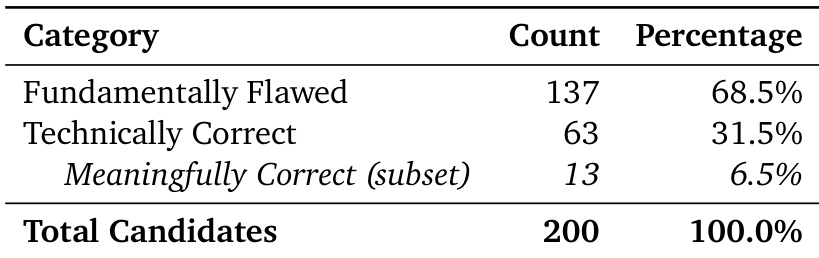

- In testing 700 Erdős problems, Aletheia generated 212 candidate solutions; 63 were technically correct, but only 13 addressed the intended problem meaningfully — 4 of these represented autonomous or partially autonomous novel solutions.

- Ablation studies showed Gemini Deep Think (IMO scale) solved 8 of 13 Erdős problems Aletheia solved, using twice the compute, and partially reproduced results from research papers, indicating Aletheia’s tool-augmented approach adds value beyond raw scaling.

- AI remains prone to misinterpreting ambiguous problems, favoring trivial solutions, and hallucinating or misquoting references — even with tools — revealing qualitative gaps in creativity, depth, and reliability compared to human researchers.

- Most AI-generated math results are brief and elementary; success often stems from technical manipulation or retrieval rather than conceptual innovation, and human oversight remains critical for novelty and rigor.

- When prompted to adapt solutions to IMO standards, the model successfully rewrote a proof using elementary techniques, achieving full rigor — showing adaptability under constraint, though initial attempts relied on unproven advanced theorems.

- On IMO 2024 variants, the model solved Problem 3 at 2^7 scale (with minor error) and Problem 5 at 2^8 scale, using novel, non-visual, state-based reasoning — suggesting first-principles derivation rather than memorization.

Results show that when evaluated on 200 candidate solutions for open Erdős problems, the majority were fundamentally flawed, while only a small fraction were both technically and meaningfully correct. The model frequently produced solutions that were mathematically valid under loose interpretations but failed to address the intended mathematical intent, highlighting persistent gaps in understanding problem context. Even with verification mechanisms, the system remains prone to misinterpretation and hallucination, limiting its reliability for autonomous research.